During one of the trips to the Transmara, while camping next to the Mara River, I had the surprise visit of the Manager of the Mara Buffalo Camp. As this had never happened before, I prepared to hear that I was not allowed to camp near the camp anymore so we stopped setting up our camp and went to meet him. I was wrong. He was a friendly Swiss that came to give me some good news.

He explained that at a rocky outcrop nearby there was a female leopard with two cubs that, unusually for East Africa in general and the Maasai Mara in particular, was very relaxed and let you watch her and her cubs without getting scared by human presence. He even offered to take us there at that precise moment if interested as he was taking a friend with him for that purpose. We instantly forgot what we were doing, jumped on the car and followed him!

After driving towards the reserve, we arrived to a rocky gorge where there was a cave high in the rocks where, to our great surprise we found a small leopard cub resting at the entrance. He said that the mother may have been hunting or, perhaps, sleeping inside, together with the other absent cub. We could not believe our luck and after waiting for a while we thanked our Swiss benefactor profusely and left him in contemplation as we still needed to set up camp, cook and rest to continue with our journey the following day.

The leopard and her cubs became an added attraction to our frequent journeys to the Transmara and we found her again a few times during subsequent trips until one day she disappeared. For a few weeks we did not know what happened to her until, again by chance, found her again later, together with Jonathan Scott. The now well known photographer, film maker and book publisher was not that well known then as he was starting his rather successful stay at the Maasai Mara.

Jonathan was watching a female leopard with young cubs with all his equipment on the ready as the cubs played and the mother rested up a rocky outcrop. We learnt that it was the same female and after that encounter we saw her a few more times. The trick was to find Jonathan’s green car when driving through the general area where the leopard dwelled! It was clearly easier than looking for her!

Relaxing…

I still recall one day when we found the leopard family in a very playful mood up and down a beautiful fig tree. It was such fun to watch them at play that I only stopped taking pictures the moment I ran out of film! I was really excited and very pleased with the pictures I had taken, although in those days you needed to wait until they were developed to see the results.

Before leaving, we approached Jonathan who we had met also at Kichwa Tembo Camp earlier and, feeling pleased with myself, I made a comment on how great what was taking place was and mentioned that I had taken lots of pictures as it was a fantastic opportunity. Jonathan listened to me and then gave me a reply that I have had in my mind since then: “I have not taken any pictures because the light is wrong”.

My heart sunk and I left crestfallen and in disbelief. When back in Nairobi the moment of truth of the pictures came I must confess that Jonathan had been right. Although some pictures were “rescuable”, the majority showed cat silhouettes against the sky! Later on, when I got Jonathan’s books I realized what he meant that day as the quality of his work is frankly superb!

As for us, despite our poor pictures, the memories remain and they at least serve the purpose to bring these back and to stimulate me to write posts such as this one!

Surprised in the open.

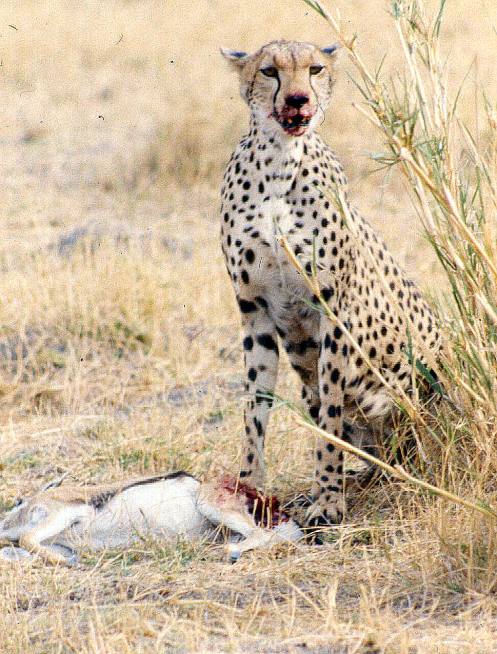

Young cheetah in the Nairobi National Park, Kenya.

Young cheetah in the Nairobi National Park, Kenya.

Frankly, I thought it would be easier to spot!

Frankly, I thought it would be easier to spot!

A leopard it was! A large male, that walked passed us and, arriving at the water it crouched to drink to placate its thirst. After a few minutes it walked off, marking a few key spots as it went slowly up the bushy riverbank. We followed it and saw it on and off as it walked up the dunes until we did not see it anymore.

A leopard it was! A large male, that walked passed us and, arriving at the water it crouched to drink to placate its thirst. After a few minutes it walked off, marking a few key spots as it went slowly up the bushy riverbank. We followed it and saw it on and off as it walked up the dunes until we did not see it anymore.