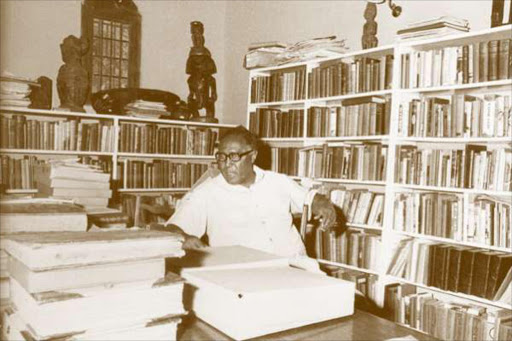

I will not tire repeating that Alan Young was the principal driving force behind the research on Theileriosis in Africa and I still regret its untimely passing in 1995 that resulted in a crippling blow to our progress in the understanding and controlling the disease in Africa.

Apart from being very intelligent, Alan was a “hands on” researcher that enjoyed fieldwork and a good laugh. During the few years we shared in Kenya there were a number of great working moments and achievements as well as some amusing ones. As this is not a scientific blog, I will share with you some of the latter that I still remember.

Although he was always writing and publishing scientific papers and work was his passion, Alan still managed field trips and he loved to visit Intona. As I described before it was Alan who brought me to the ranch in the Transmara for the first time after my first trip to Mbita Point with Matt [1].

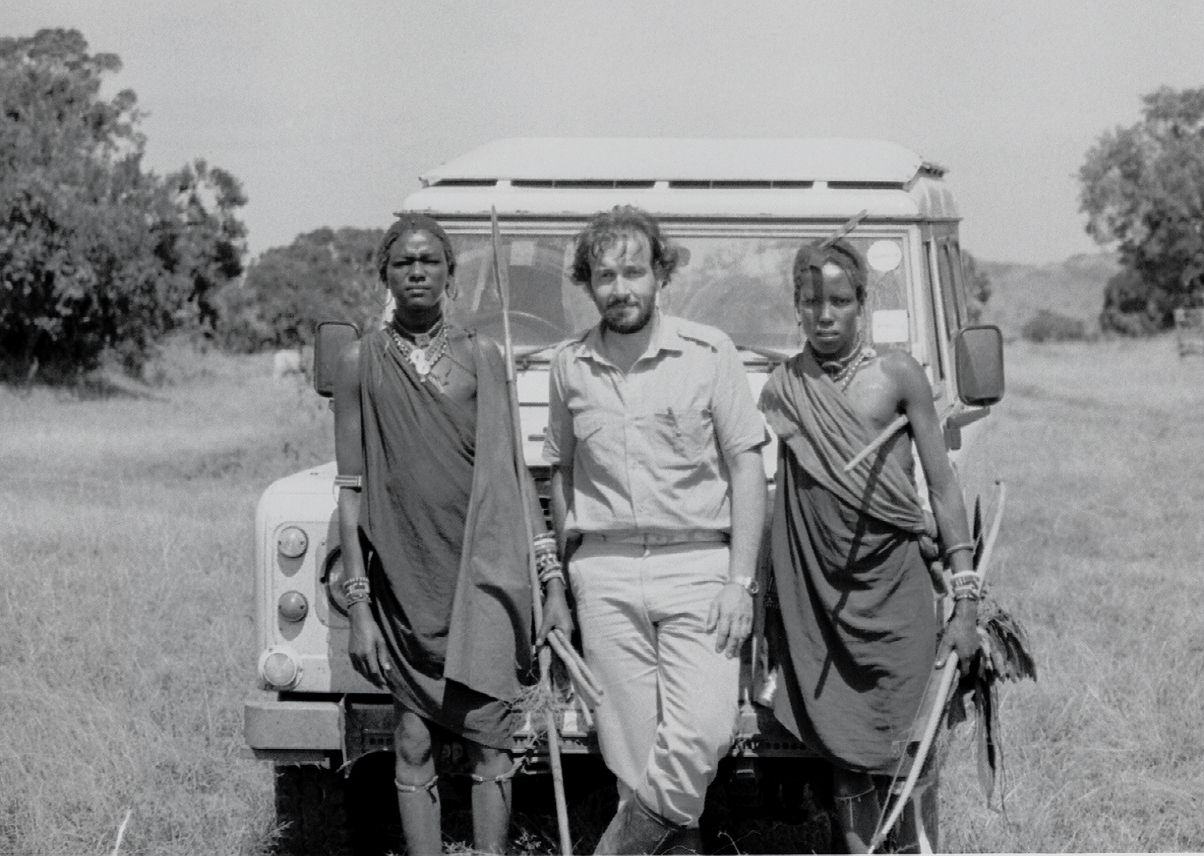

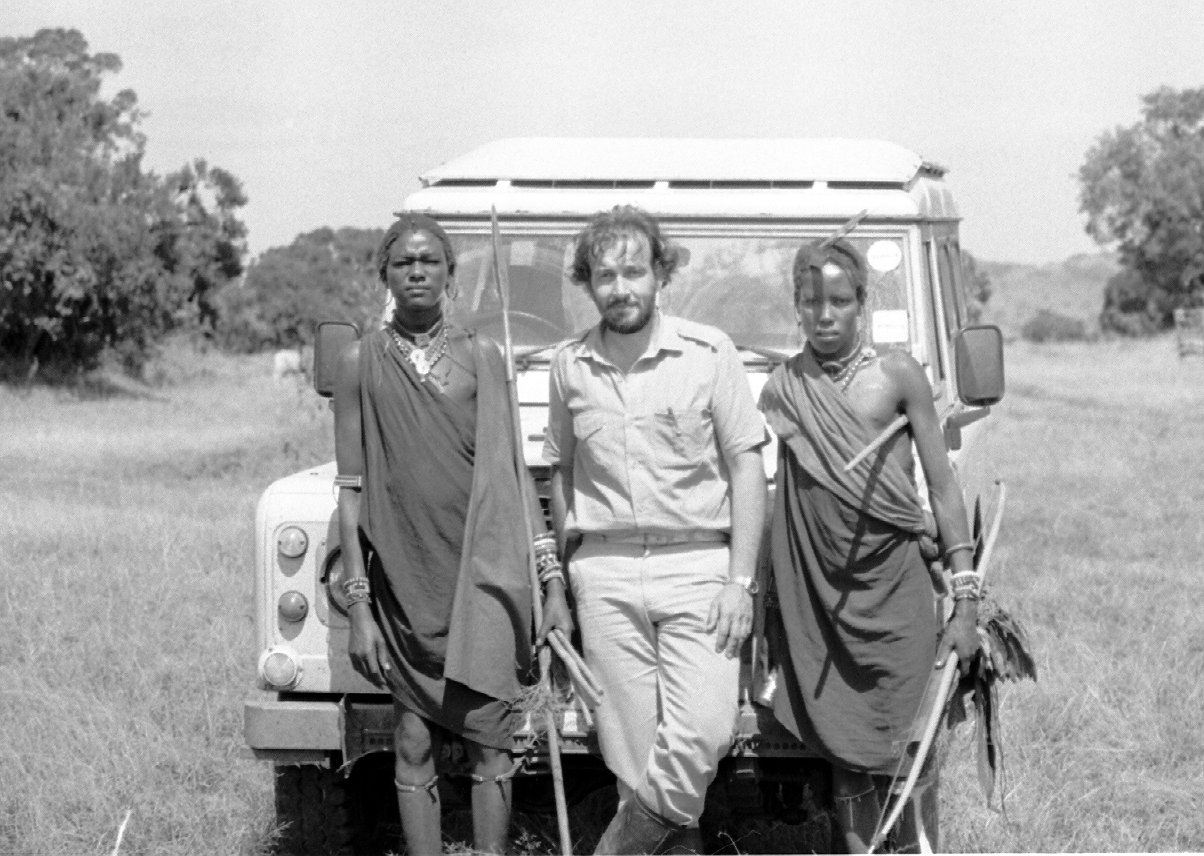

Alan inspecting the cattle at Intona ranch.

I needed his expertise to protect cattle against Theileriosis so I could stop applying acaricides to them for my trial. He was always busy following up immunized animals, a procedure that required many hours behind a microscope checking lymph and blood smears to detect early signs of the disease and take appropriate action.

Luckily, we had a cohort of well-drilled KEVRI and ICIPE technicians that would stay at Intona monitoring the cattle as well as the tick work I was involved. Some of them were the protagonists of some incidents that I believe are worth narrating.

During one of my first trips from Muguga to Intona with Alan and the herdsmen, in particular a very funny one called Ben, we left Muguga at about 09:00hs. Not a very early start but the herdsmen needed to wait for the Government’s cashier to give them their per diem for the days they would be in the bush. This meant that we needed to stop on the way to get their provisions for the entire spell that they would be out.

So, after getting cooking oil, ugali [2] and cabbages, we stopped to fill-up the car at the main Nairobi to Kampala road. Alan dealt with the fuel, I did nothing but walk about while the herdsmen went off to get paraffin for cooking.

After a while we were ready to depart. While Alan waited for the change from the cashier I got in the car and noted a rather overwhelming paraffin smell. Thinking that one of the herdsmen containers was still dirty in the outside I kept quiet thinking that it would soon dry up and the smell would stop.

Alan came in and he immediately detected the strong fumes and asked the herdsmen at the back of the Land Rover to check their paraffin containers. They both replied that all was in order so we moved on with our windows open. However, as the stink continued, Alan decided to stop about a kilometer further to have a look. He was not amused when he found that Ben was clinging to his plastic paraffin can. Alan noted that he was trying to block a leak with his finger! It was necessary to return to the petrol station to get a new container before the journey resumed! Luckily, over the long journey we shared a great laugh with Ben over the issue.

Once my work started at Intona I was there often and regularly to manage the tick trials I was running. Kiza, the resident veterinarian at the ranch, supervised Alan’s work but also looked after the numerous Murumbi’s pet dogs that kept him very busy. The arrangement with the cattle was that Kiza would radio Alan in case of any complication was detected.

So, during one of my stays at Intona, Alan turned up to deal with some abnormal cattle temperature readings. I was at a particular busy time and did not know what was taking place so here I reconstruct the story from the various participants.

The monitoring of cattle immunized against Theileriosis included recording daily body temperatures and taking blood and lymph node smears to check for parasites in both tissues. There was a book where these findings were recorded daily.

At that particular time, John, one of the hard working KEVRI staff, was in charge of monitoring the cattle. Immediately upon arrival Alan asked for the book where the daily cattle temperatures were recorded and started to go through it with Kiza and John himself. The issue was that, for the last four or five days there were some unusual temperature readings, different from the earlier trend. The experienced Alan smelled a rat so he asked John to repeat the temperature checking for that day to compare with those in the book and see if he could detect anything.

After the request, an inordinate amount of time elapsed before John started checking the animals and, eventually, he came to reveal that all the thermometers had broken and that, over the days in question, he had taken “temperature estimates” of the animals based on how they felt to the touch under the tail area!

Later on, when things settled down, over a beer Alan narrated the event to me and he was very amused to the point that he coined the term “John’s finger test” to describe what had happened! Although we never quite knew about the real procedure employed by John, we had a good laugh and both his working mates and us forever teased John about this incident.

This anecdote of a time when we were applying identification ear tags to cattle at Muguga confirms that I was not the only one that had difficulties to understand Alan. We were using new ear tags and noted that we had forgotten the special pen to write on them known as the Magic marker as it would write on plastic and the paint would last long.

So, Alan asked one of the older workers called Ernest to bring it. After about twenty minutes Ernest had not yet returned although the office was quite near. Alan and I were getting anxious and wondering what happened as this was a routine procedure and we needed to get on with more important work.

When I was about to go and check we saw Ernest walking very slowly towards us trying not to spill the water from a plastic washbowl. We looked at each other fearing some “cock-up”; the term we normally used for these eventualities. Alan echoed my thoughts when he asked Ernest “why did you bring this if we asked you for the magic marker?” “Oh”, Ernest replied, “I thought you wanted “maji moto”, KiSwahili for hot water. The delay was now clear and he rushed to get the pen while we both burst out laughing.

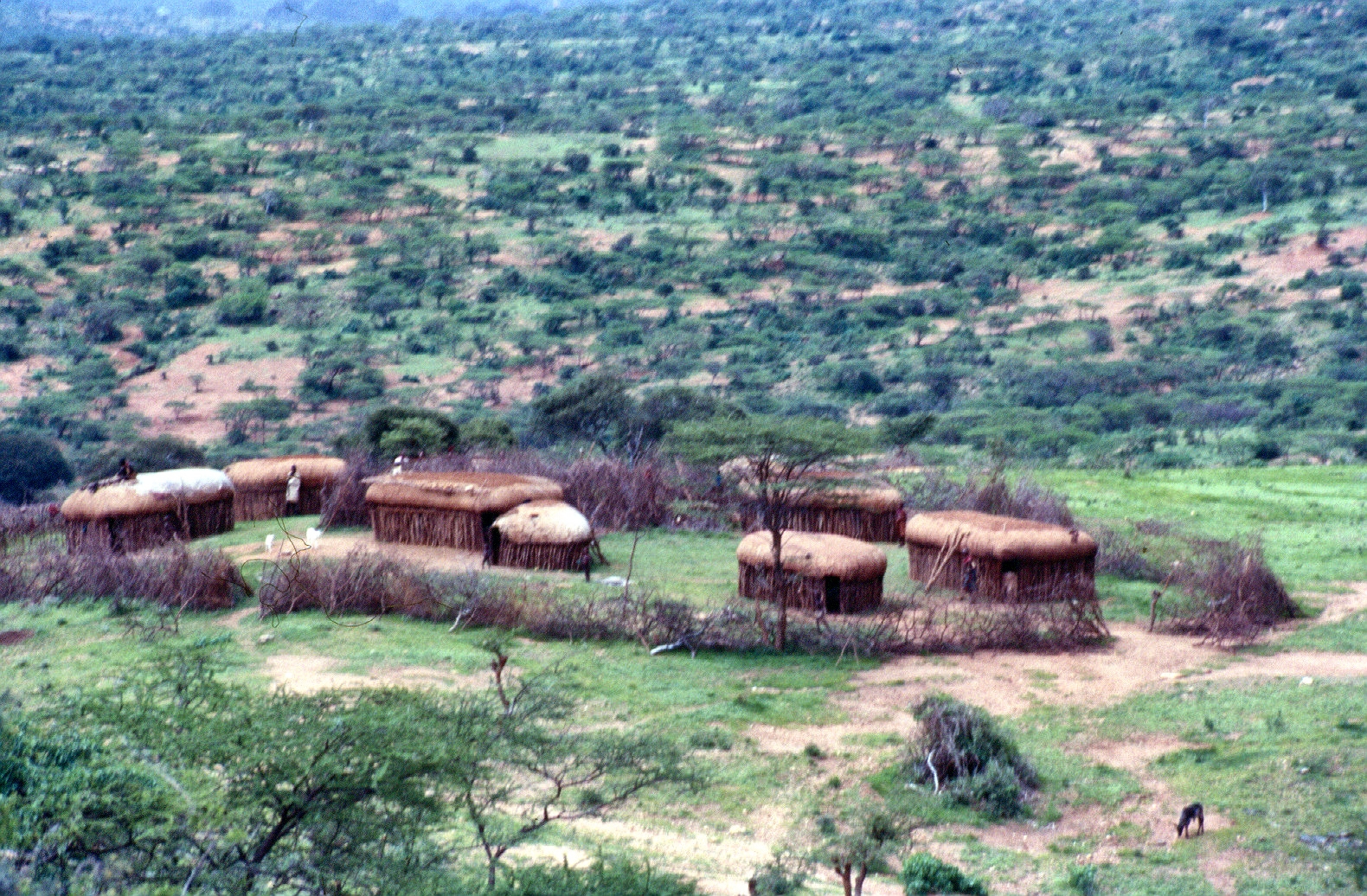

After a few years I completed my FAO assignment but remained in Kenya as a scientist with the ICIPE and my collaboration with Alan continued although my work had shifted to cattle resistance to tick infestations. I continued visiting Intona with a new experiment that required the building of a special paddock.

It was very important that the wild animals were kept out and the cattle inside the paddock for the trial to succeed. We were not only dealing with African buffalo that were common at the ranch but also with elephants that at times would literally walk through Intona and we knew that they would not be stopped by a normal fence!

Building the paddock.

The paddock being used.

So, Alan had the idea of setting up a strong paddock with an electric fence. Alan was traveling frequently to the USA at the time and brought a couple of solar powered electric fence units capable of delivering 11,000 Volts pulses of very low amperage (safe as high Amps are the ones that could kill you) but the high Voltage will “only” hurt you!

The Solar-powered units for the fencing.

The solar powered electric fence unit installed in a protective box.

The day came to connect the fence so that the trial could start. We needed to confirm that the solar-charged batteries were delivering the correct electricity current according to the manual. For that purpose the equipment came with a very fancy tester that Alan would use. We had left the unit charging from the day before as advised by the makers.

Although it rained most afternoons, because of the influence of Lake Victoria, there was sunshine from sunrise to about 17:00 hs, enough for charging the batteries. So, Alan, the herdsmen and myself, after listening to the pulse clicks at the unit, went to the fence to finally test its power.

Alan applied the terminals to the wire and, before I go on, I must tell you that what took place happened very fast so I may have missed some details as I was looking at the reading in the tester. I believe that first there were some sparks but in any case, the tester disappeared from my field of vision together with Alan that proffered a rude epithet while being thrown back from the fence and falling on his bump!

“Pole sana”[3] said the herdsman and I also muttered a rather useless “oh, sorry!” Alan sat on the ground, rubbing his right hand that was still holding the charred remains of the tester! Our concern about his wellbeing evaporated the moment that Alan burst out laughing and we all relaxed learning that he was still his usual self even after the shock!

Probably the rain that fell the day before had had some impact in the transmission of the electricity pulses that, somehow, got to Alan and not to the tester. From that day on we assumed that the fence was powerful enough and no further checks were ever performed again for lack of volunteers and a tester!

While performing field trips with Alan he kindly lent me his Land Rover as part of our collaboration until some years later ICIPE finally decided to buy a similar one for our work.

Alan’s car was heavily used, as we not only traveled to Intona but also Busia and Laikipia to name the most common ones. Although I never noticed it, years later during a visit while I was already out of Kenya, I managed to meet with some of our former herdsmen who as one of the events they remembered was that we had been carrying Chang’aa, an illegal drink! I was astonished when they explained me how it happened.

Alan’s Series III Land Rover had two jerry cans fitted at the front of the car. As we considered carrying petrol there too dangerous in case of an accident we kept the cans empty and, frankly, we forgot about them.

Chang’aa, also known in various languages as kali, kill-me-quick, Kisumu whisky, maai-matheru, machozi-ya-simba and others, was (and still is) the name given to distilled spirits in Kenya and the manufacture, commerce, consumption or possession of it was, at the time, illegal and punishable with heavy fines and even up to two years in prison! [4].

So it resulted that the guilty herdsmen would buy Chang’aa in the field, place it in the jerry cans and “import it” under the cover of our work to Nairobi where they would, I imagine, sell it for a handsome profit!

So, without our knowledge, our Land Rover (and us!) was used as a “mule” in the rather clever operation! I never had the chance to comment this with Alan as I learnt about it after his passing so I am not sure that he ever found out about it.

Alan and I shared the passion for soccer. While this should not surprise you in my case, as I come from Uruguay but for someone from Northern Ireland, not a great soccer nation, it was remarkable at least in my book. We shared our soccer interest with Walter, the then Director of KEVRI, Muguga, and this was a frequent topic during our many morning tea breaks at the Institute. Walter was the Chairman of one of the main teams in Kenya, AFC Leopards, but also followed football worldwide.

In 1989, living and working in Ethiopia, I attended one of the FAO Expert Consultations on Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases in Rome where I met Alan and, during the meeting, we learnt that there was a football match the coming Sunday. The meeting was ending on Friday so we agreed that, return flights to Africa permitting, a soccer match of the Serie A League was a must.

Because I could speak some Italian I dealt with the organization of the outing once both checked that our flights would leave on the Sunday night. So, I confirmed that Lazio, one of the two teams from Rome, was playing Fiorentina (from Florence). The game would take place at the Stadio Olimpico, the main arena in Roma built for the 1960 Summer Olympic Games.

I still remember that it was Sunday 21 May 1989 when, before lunchtime we left the Sant’ Anselmo hotel in the Aventino area of Rome and walked to the bus stop as advised by my Roman contacts. The bus was empty as the stop was the start of the line and, seated, we were soon on our way. About half way a crowd of Lazio tifosi (fans) dressed for the occasion and carrying lots of flags and banners filled the bus. They were many and about half of them were left behind when the doors were closed!

We were really packed, almost worse than in a Kenya minibus! Surrounded by people dressed in their team’s pale blue shirts I felt like going to a match where the “celeste” (pale blue) of Uruguay was playing! After a while the tifosi started to jump all together and to move sideways… We look at each other in disbelief and grabbed whatever handle we could, as the danger of the bus toppling sideways was a real one!

Feeling like survivors, we were the last leaving the bus. It was about an hour earlier and it was filling fast. We approached the usual ticket sale points and they were all closed, except for the really expensive ones. We were in trouble, as we had not planned for such expenditure! Far from giving up, we looked for a quiet corner and counted our cash realizing that it would be either soccer or lunch! Luckily we already had the return bus tickets.

Without hesitating we agreed to skip lunch so two starved and penniless people entered the grand stand that afternoon! The attraction for me was that Rubén Sosa, a Uruguayan that had a distinguished career as a fast attacker with a great goal scoring ability and exact passing. He is considered by many as one of the best soccer players Uruguay has produced in the second half of the 20th Century!

The match was even and entertaining until early in the second half Lazio was awarded a penalty that Sosa converted into a goal and Lazio won. The people in the stadium went wild and, when he was replaced at the 89th minute, got a standing ovation (that included us!). We were really happy and the occasion gave me good ammo to tease Alan in the future about my South American origins!

[1] https://bushsnob.com/2015/06/01/intona-ranch1/

[2] KiSwahili for white maize flower, the staple food in Kenya.

[3] “Sorry” or “very sorry” in KiSwahili means

[4] Kenyalaw.org/kl/fileadmin/pdfdownloads/…/Changaa_Prohibition__Cap_70_.doc Consulted on 25/11/2018.