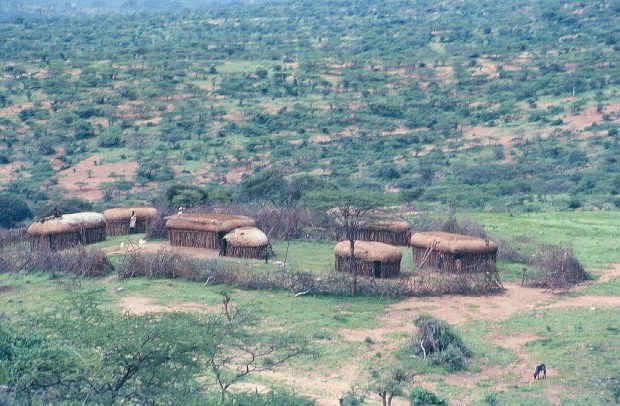

The Athi plains, adjacent to the Nairobi National Park (NNP), was another area we visited on weekends. The place was sprinkled with Maasai manyattas and the sound of cowbells accompanied the movement of their herds while grazing. It was open grassland where giraffes, wildebeests and Thomson’s gazelles would be usually found. Occasionally we would spot small flocks of ostriches intermingling with the herbivores.

A Maasai manyatta.

Being rather obvious, ostriches could not hide very long from taxonomists and as early as 1758 Linnaeus had already labelled them as Struthio camelus. More than one hundred years later, more detailed observations followed and it was realized that Kenya hosted two different ostriches: the Maasai ostrich (S. c. massaicus) with a pink neck and its cousin, the Somali ostrich with a grey-blue neck. As the latter dwells in North-eastern Kenya, in the Athi plains we saw the Maasai sub-species.

A male Maasai ostrich (S. c. massaicus).

Somali ostrich (S. molybdophanes) photographed in the Samburu Reserve.

By luck one day while driving cross-country with our friend Paul enjoying the views and looking for a picnic spot our route was interrupted by a deep ravine. We needed to follow it for a while to find a crossing point when, lo and behold, at the bottom of it we spotted a female ostrich sitting on a nest and surrounded by eggs.

The female sitting on her eggs. The “rejected” eggs are seen surrounding her.

Judging by the couple dozen eggs or so that were not covered, we assumed that she had plenty more under her. As those outside would inevitably rot after the incubation was completed a maximum of forty days later, we decided that, once the adults and chicks moved off, we would collect some of the left over eggs that would be dead by then for emptying as we judged that there were enough to be shared with the Egyptian vultures and other possible predators.

Before I go on with the story, it has been reported [1] that, in general, wild ostriches lay their eggs in communal nests. Up to seven hens lay up to thirteen eggs each in the same shallow nest in the ground. Apparently, the “major” hen guards and later incubates the nest, helped by the male. As the female can only cover about twenty eggs the surplus eggs are moved out about 1one to two metres from the nest where they perish. But this is not all, the senior hen apparently recognizes her own eggs and keeps them!

Not having GPS technology at our disposal, we fixed the place as per the trees available and decided to have a look a couple of weeks later.

Somehow we forgot about the incubating hen but Paul did not and he visited the nest after a week and confirmed that the female and the eggs were still there. The following weekend, my wife and I decided to attempt finding the nest again. Surprisingly (we are not very good at bush driving!) we found what we thought was the right ravine but there was no trace of the female.

As usual, doubting that this was the right place we drove further along the donga until eventually we found the nest. Lots of broken shells were proof of a good hatching that we estimated in more than fifteen young! At the periphery of the nest, only a few eggs remained still intact and, as planned, we collected them (six in total) and took them home, hoping that they would not break “en route”!

A couple of days later Paul came to visit and told us that he had bad news: although he had found the nest, all the eggs had gone! So, he believed that someone had been there before us. After a good laugh, we showed him the eggs. Pleased, he recovered his normal good humour and mentioned that he will organize a garden “Ostrich egg blowing event”. He will invite a few common friends.

Somehow, prior to the event Paul managed to get a portable dentist drill that- he believed- would had been perfect for the job. So, when the day came, we went to his house carrying the eggs.

Paul and I (the veterinarians) were excited about the egg emptying exercise. Other friends (including all the ladies) were indifferent and focused on getting comfortable in the veranda to enjoy their sundowners and socialize! Only Timothy, our artist friend, decided to join us and immediately took possession of “his egg”. As Paul and I were used to strong odours, we did not think much of the exercise. I am not sure why Timothy was so keen on it and it remains a question up to today!

I am sure that you are all familiar with hydrogen sulphide (H2S) the gas responsible for the smell of the very few rotten eggs you find these days of “modern” farming and expiry dates. I had cleaned many bird eggs in my youth (including rhea ones) so I was fully aware of the risks! The technique I used consisted in drilling holes at both ends and -when the eggs are still liquid- blow through one hole to force the egg contents to come out through the other one. Not so easy with a large ostrich egg!

We set up the drill and lined our eggs very professionally on a table, at the other end of the veranda, as far away from the other guests as possible and Paul, claiming to be an expert on the dentist drill, started boring the first one with Timothy in attendance, holding his egg. The drill worked faster than anticipated and the egg eruption caught us (and the other guests albeit far) totally off guard!

The three of us failed to move away from the effects of the explosion as fast as the other guests that, luckily unharmed but proffering very bad words, swiftly trooped into the house and locked all openings to the veranda! We, the unsung heroes stayed put, covered by stinking egg gunk to complete the operation that involved repeating the process on four more eggs and then blow through them to empty them! Timothy had gone paler than his usual self and instants later started to retch while still holding to his egg with both hands.

“I think we will be better off on the grass” I said. Paul agreed and found an extension cable to plug the drill. We decided to use a garden hose to flush rather than blow the eggs contents so we went in search of the garden hose. As we walked in the garden we heard a noise and soon enough we met the retching Timothy seated on the grass while chipping at his egg with an awl. “Timothy”, Paul said, “do you want to prove something?” Amazingly, Timothy did not or could not reply but continued struggling.

We were about to finish washing our eggs clean when we heard a thud and heard loud swearing followed by more retching. Timothy had unplugged his egg! We helped him cleaning it. We had completed our job!

While carrying the eggs back to the house we got under proper illumination and we could only laugh at our condition while having a summary wash. The smell was so strong that we clearly did not understand it in its full intensity until we tried to enter the house. We found it locked and its occupants would only talk to us through locked doors or windows accompanied by rather rude sign language. Lengthy negotiations ensued. We protested that it was too cold to wash outside but our pleading was totally ignored so we had to agree and suffer the cold water. Finally under pressure we agreed to their demands that we would have a thorough wash with the hose outside and only then we would be allowed to enter the house straight to the bathroom while the guests moved to the kitchen for the duration of our showers!

We heard the door unlocking and someone said “You can come in now but straight to the shower, please” . We obeyed and, half naked, we went in under the scrutiny (and laughter) of the others. There was a small incident when Timothy was asked to leave his egg outside and he refused at first but, eventually he relented. We were then given towels and some of Paul’s clean clothes to wear for the evening.

Although we showered intensely and made use of Paul’s favourite perfumes, the smell was tough to remove so, although we were given the all clear to dine, the three of us were eventually seated on a table away from the clean guests in a kind of “smell quarantine”.

The operation resulted in three eggs for us (for having collected them), two for Paul and one for Timothy (for his brave behaviour and also because we could not have taken the egg away from him!). The eggs still exist and are sitting on some special stands we eventually got made in Zambia for them. They look nice and do not smell at all now.

[1] Bertram, B.C. R. (1979). Ostriches recognise their own eggs and discard others. Nature 279, 233–234.

Reblogged this on Janet's Thread 2.

LikeLike

Oh, I think I have seen that very egg at your place 🙂

LikeLike

I am sure! We still keep them.

LikeLike

Great story! Certainly the most grotesque incidents make for the most entertaining stories :)) When I first started out as a farrier, many years ago, I had a bucket to hold my shoeing tools. I was working in HOT Bakersfield, California, area for a lady with a horse at a PIG FARM. I went to my car to fetch something, came back, and discovered my tool bucket filled with urine! The horse had relieved himself just over the bucket, and moved aside, so I had no idea . . . until I drew out a pissy tool! Washing the stuff off each tool, muttering to myself, the fragrance of the heat and pigs joining the fun. All I could do was tell myself that I was guaranteed a great story,

LikeLike

Great anecdote! I can imagine your surprise at getting the tools out! Thank you for the comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And the smell . . . :))

LikeLike