As you have probably realized, we were not following the Bedele social scene for several reasons that you can also guess, language and cultural differences, isolation at the laboratory and the feeling that not much was happening.

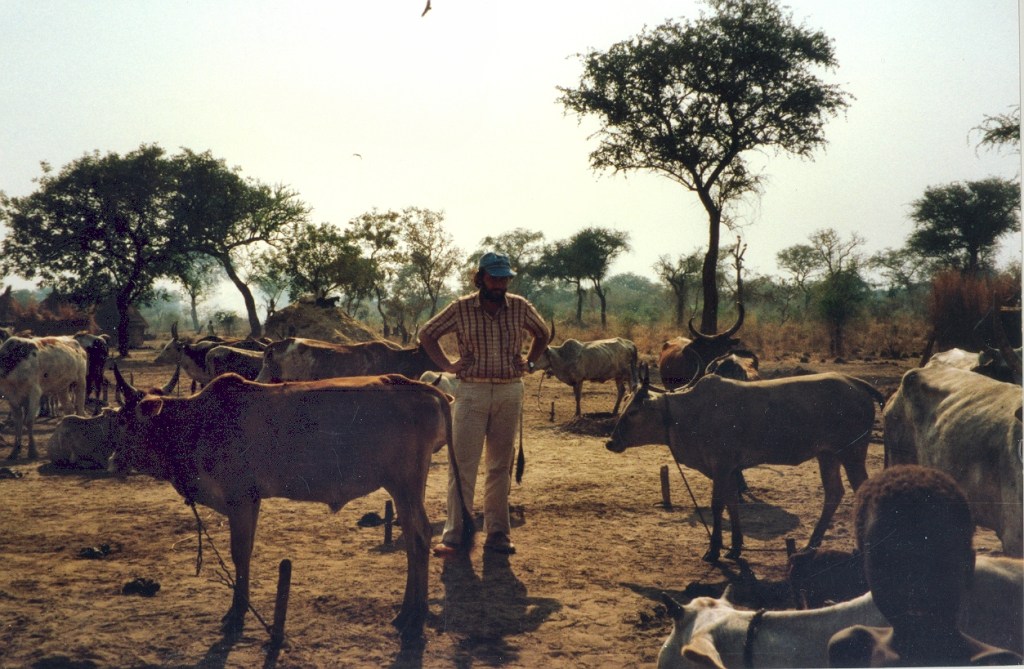

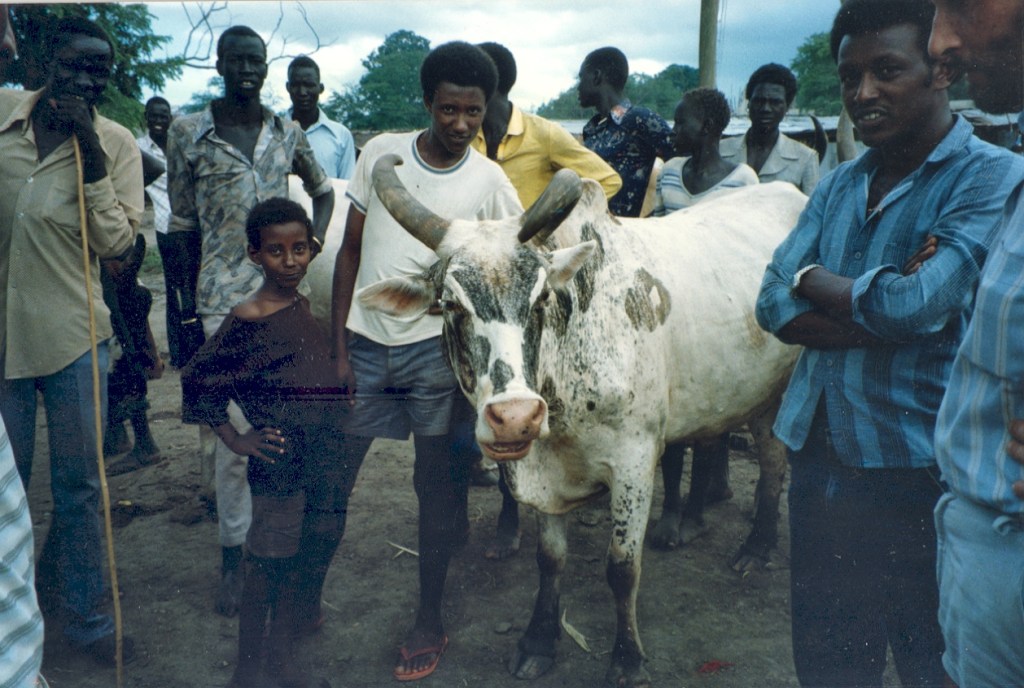

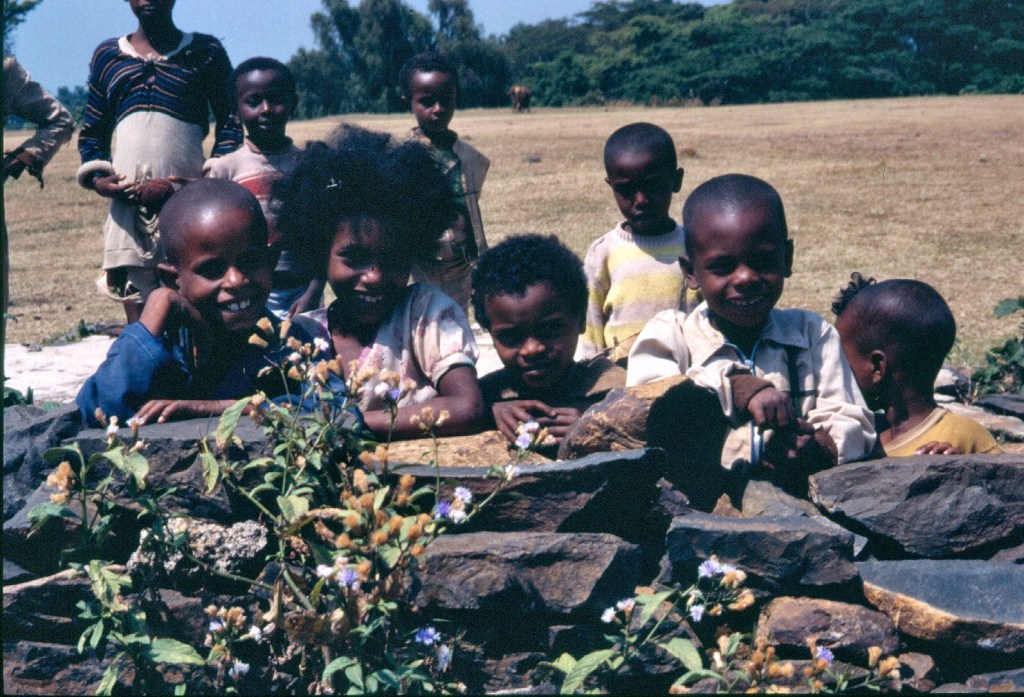

The weekends that we did not go out exploring the surrounds, we visited the farmers market and bought what we could find there while having a look at the various activities that went on there, in particular the livestock sales as there was a lot of loud haggling and discussion going on that was quite entertaining for a veterinarian. It was also new to us that farmers would arrive to the fair riding a mule or a horse but we soon learnt that for many villages this was the only way to move around.

One time, while leaving Bedele in one of our weekend escapades, we noticed an aid lorry parked a few kilometres outside the town that we thought was being offloaded there “unofficially” and, as expected, when we were spotted, all activity ceased. However, we suspected that some of the relief food was siphoned out for other “beneficiaries” although we did not know who!

Following on the above, with the passing of time we discovered a second market. One that did not function in the open air but under a roof and that offered numerous food and food-related items, clearly coming from what we had seen earlier on the road. There was flour from origins as different as Canada, Italy and Argentina and cooking oil of different kinds, including olive oil from Europe. We also saw bags and bags of chocolates and high energy biscuits of the type that are consumed while on a climbing expedition and literally hundreds of humanitarian eating and drinking kits still in their original plastic wrappings showing their unsuitability for the recipients.

Although the large food items were likely to be those diverted from lorries, the other stuff was most likely traded by the refugees themselves that did not need them or did not know what to do with them! This market, until it burnt down a while later, was an important source of food for the Bedele inhabitants that were able to get some stuff that was otherwise unavailable. So not everything was lost!

Most of our news were related to life in the laboratory and our neighbourhood. Among these, the birth of Jan and Janni’s son Winand in The Netherlands was great news and their arrival to the laboratory was a motive of great joy. He was the object of attention of everybody, in particularly of the resident ladies, including Mabel, that took turns to look after him.

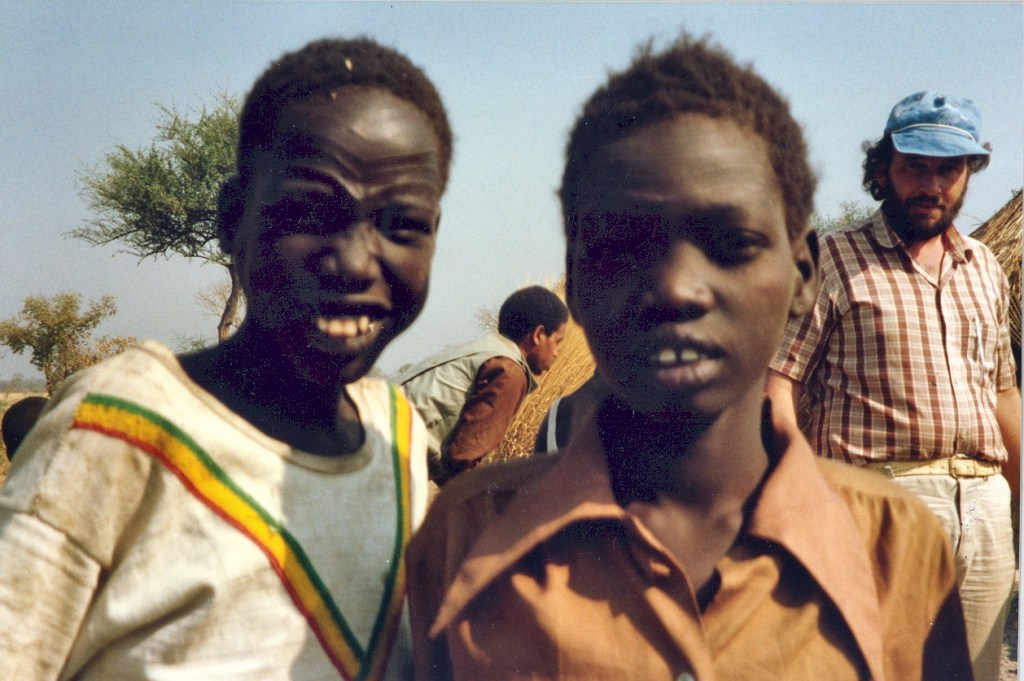

We did have a number of visitors from abroad. The first one arriving was Giuseppe, an Italian veterinarian with an interest on tsetse and trypanosomiasis that came to work with Jan for a while. Although we saw him briefly, our meeting was the start of a friendship that lasts until today. Later, our friends and safari companions from Kenya François and Genèvieve also came and with them we did a bit of sightseeing, mainly around Bedele that we all enjoyed.

Finally, towards the end of the project Paul, my FAO backstopping officer came to see the work and to assist me with the writing of a project extension to continue the work although we knew that UNDP had no intention of continue funding it as I explained earlier. However, we did write a new project and, eventually, we got some funds from the Danish Government to continue the activities, particularly on tick-borne diseases.

Although mostly unknown to us, some events that took place in Bedele were rather dramatic.

There was a great commotion at the laboratory when a serious accident took place on the Metu road just outside Bedele and, of course, we all went to see what had happened. As, while we were getting there all was said in Amharic I was not entirely clear of what had happened, so I went fearing to find lots of casualties.

Although there were fatalities, luckily, there were not humans! A bus full of passengers had hit a cattle herd and it had killed eight of the animals and their bodies were strewn along the road. It was a sad incident but with a note of humour as well. We spotted our butcher already negotiating with the owner of the animals to buy them cheap! Of course, we made sure that we did not buy meat for a few days afterwards as its toughness would have been more than the usual chewy nature!

Although far away from Bedele, the civil war permanently influenced our lives beyond the travel restrictions and shortage of fuel that I described earlier.

One day we drove through Bedele and there was hardly anyone in town. Surprised I asked what was the reason, but I did not get a clear reply. I was told that people were at some religious ceremony at another town and other stories. Unconvinced, I went back to the laboratory and discreetly asked one of my trusted colleagues at the project. “Bedele people had learnt that the military are coming soon to recruit soldiers and the young men are hiding in the forest” he said and then added “they do not wish to go to fight in the north!”. This event was repeated a couple of more times and I do not know how many people were really recruited. However, there must have been some success as the army training camp near Jimma was always busy!

The war also complicated the lives of the Ethiopians working at the laboratory, so they needed to be extremely careful when voicing any political opinion. We accepted an invitation to eat spaghetti at a neighbour house one day. Dinner was a pleasant affair but, as the evening advanced, tension arose between the host and one of the commensals over the political situation. To our dismay the discussion got hotter and the host got rather vehement on his attack to the Government to the open (quite rare I must say) dislike of the visitor.

Aware of the situation we retreated as soon as we deemed it to be polite and the meeting ended without much more ado but clearly on a wrong note. Although we talked about this for a few days, we soon forgot it.

However, after a few weeks we learnt that our host -that happened to be a nurse- was mobilized by the army and sent to the war front! Luckily, he survived the time he was there, and we saw him again before we left the country although it was apparent that he had suffered, both physically and mentally, the time spent at the war front.

The other time when I felt the difficult situation of the Ethiopians that did not agree with the regime was when one of my counterparts from the project and myself were traveling to Rome for a meeting. My colleague managed to get the innumerable clearances needed in time and, finally we found ourselves on board of the Ethiopian Airways plane to Rome.

Aware of his concerns, once we entered the plane and found our seats I said casually “Now you can relax”, “Not until I see Addis from above” was the reply I got. I thought that he was exaggerating but, as if by some kind of magic act, two people looking like plane clothes police or secret service boarded the plane and walked down the aisle towards us.

I noticed that my colleague became very quiet and quite pale but, luckily, it was not him they were after! So, when the plane took off, he regained his usual cheerful ways and only then he looked relaxed. I must confess that I thought that, once out of the country, he would not return with me to Ethiopia but I was wrong and we continued working together until the end of the project.

Sometime in 1989, the construction of the Bedele beer factory started and we had the arrival of a Czech engineer that was in charge of the building. He became “forengi” number six (counting baby Winand of course) in Bedele and we saw him sometimes although we left a good while before the now well known “Bedele Beer” started to come out of the production line.