While in Kenya we always wanted to explore the north on a camel safari but the cost was an important deterrent so we left Kenya for Ethiopia in 1988 without achieving this goal. However, two years later, while on our way to a new job in Zambia, we stopped in Kenya for a while and decided to join forces with our friend Susan and to go for it.

She knew a company [2] that organized these activities and made the bookings for the three of us. A couple of days before we were to depart, some unavoidable work commitment cropped up and Susan were unable to go. She volunteered her very good friend Gai to come with us. We had met Gai a couple of times while visiting Susan during our earlier Kenya days. Although we did not know each other that well we agreed to travel together.

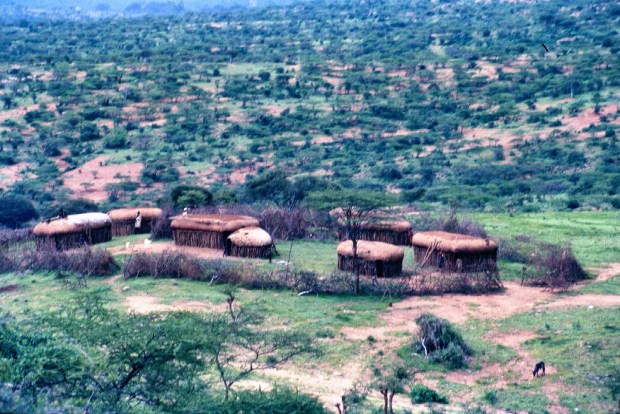

We drove Susan’s car to Rumuruti and from there we were taken to the company’s base camp where the journey was due to start. The idea was to travel for four days along the Milgis River and then get picked-up by a car and taken to Rumuruti to spend the night, collect our car and return to Nairobi the following day.

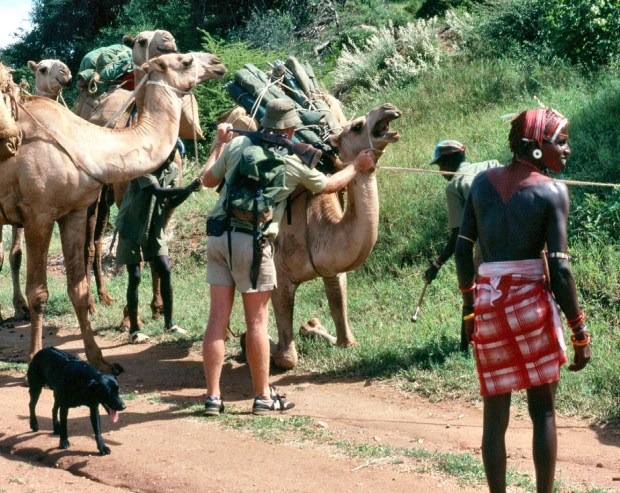

We arrived in the morning and already the camp showed great activity as the camels, really huge when you stand next to them, were being loaded. Dromedaries are the tallest of the three species of camel and adults can reach 1.7 to 2 m at the shoulder and weigh between 300 and 600 kg.

While the beasts complained loudly while their loads were tighten we were given a brief on what to expect and other useful information for the trip. With us was a group of four Europeans that kept very much for themselves, and a British couple that, as expected, was very polite!

We learnt that the idea was to walk or ride for a few hours each morning, have a lunch break and a rest and continue for another two to three hours until we arrived to the next camp that would have been organized ahead of time. We would stay there the night and the exercise repeated for the remaining days. It all sounded very civilized and we were ready to start.

There was a senior guide and a number of camp hands, most of them Samburu that, although did not speak great English we could communicate with our basic Swahili. However, we were very pleased to see that Gai was very good at it, the fruit of her many years of work as a teacher in Baringo. In any case, they were all nice and helpful so the atmosphere was positive and we started to get on well with Gai and it became clear that we would enjoy our time together.

Observing the camels being organized, we noted that they played different roles. Immediately we started making our own groups. That is how we defined camping camels (carrying tents, chairs, tables, etc.), riding camels, first aid and laggards camel (to mend blisters and pick up strugglers, just like in the cycling races!), bad camel (called Sungura [3]) and food and bar camel. The latter Gai and I attempted to follow, not because of being hungry, but the longer legged beast was always moving faster than us so we could only catch up with it at the end of the day when we did our best to lighten its liquid cargo.

Daily, the camping and bar camels would go ahead to set up the next camp while the others would stay with us and we were careful to keep our distance from Sungura that showed its bad temper at all times and repeatedly attempted to chew us, particularly Gai that, for some reason, became its preferred target!

Sungura makes sure to be heard!

A view of the camels ahead of us.

Our relations with the other travellers were going well until we discovered that the European contingent, of the kind that attach their flags to their rucksacks, had borrowed our sunblock cream without asking! This was an offence that gave us ammo to criticize them whenever the opportunity allowed. From then on we kept our suntan cream under tight control so that it would last until the end of the safari.

After a couple of days walking in Samburu country where we found numerous cattle, sheep and goat flocks, we detected that one of the members of the European group was showing clear signs of crotch rash (inner thigh rash) and walking was becoming increasingly difficult for him. We decided that camel riding would alleviate his predicament and had a go at it.

Apart from intimidating prospective predators (and riders!) by its share size and strength, camels can defend themselves very well and have a number of ways of doing so, apart from their unpleasant screaming and grunting. They can stamp their feet, kick in all directions with the four legs, bite, belch and spit so to mount on one is not something to be taken lightly.

After you overcome your ancestral fears -but always thinking, “why am I doing this?” you approach a lying down camel making sure that it was not Sungura. The beast looks inoffensive enough and with the help of the herder you take your seat in the middle of the one hump. You have a precarious siting arrangement as in front of you there is the neck and head and behind is the camel abrupt end so you need to hold on.

Once you are firmly wedged on your riding saddle the action starts by the beast standing up. This is a most traumatic event as it first stretches its back legs and, suddenly you are in danger of killing yourself by falling over its head. Before you fall, luckily, the beast stretches its front legs and up comes its massive head that misses yours narrowly and, if you are still on, you find yourself very high from the ground and in great danger of a serious fall.

I had grim misgivings about driving my camel as I was sure it would end bad for me. Luckily the handler would hold the reins and walk you following the path. The ride is very comfortable as your backside is well pampered and the animal’s gait is really pleasant, more so than horses. The position affords you a great view of the countryside over the surrounding bushes and I must admit that I enjoyed the ride.

Unfortunately this only lasted for a few minutes as my beast, perhaps sensing my dislike or because I was heavy, decided that it had enough of me and it started to walk closer and closer to the abundant thorn bushes. Then, despite the efforts of the handler, the inevitable happened and my naked legs got painfully rubbed against thorns.

That was enough for me and I immediately asked to be spared from such a torture as I would have ended without skin in my legs if I would have continued. Relieved, I descended from the beast while promising myself never to do this again

Gai suffered a similar experience and we both compared our scratches later while trying to clean and disinfect them. Mabel, as usual and to our annoyance, enjoyed the ride tremendously looking as if she had done this her entire life! She spent about an hour traveling by camel and spotting birds and animals that we were not able to see from our lower position and finished looking as fresh as ever!

Unfortunately the camel ride did not help the European rash sufferer and, from a distance we witnessed a Europeans-only meeting with the lame guy as the centre of attention. Although at the time we did not know what the outcome of the meeting was, the answer became clear when the following morning the Europeans were evacuated. Probably walking in the heat was too much for them to bear coming from a place near the North Pole!

Our party got reduced to five and we were happy that there would be more resources (read food and drinks) to be shared among the “survivors”.

Every evening at the end of the day we would arrive at our flying camp that had been set up at some chosen location by the river that never disappointed. The camping chairs were set up overlooking the flowing water where we enjoyed sundowners after our hot bucket showers.

That was the time for talking and to compare notes with the only remaining companions, the British couple. We learnt that he had been very successful with a lighting company in the UK and that he had sold part of it and, retired, were doing the best to enjoy life.

While we talked and drank, dinner was being prepared. It was simple but tasty and to be eaten under a the stars while the camels lied down and chewed their cud and the herders got ready to settle for the night among the beasts. After dinner we also settled down in the tents already assembled for an early night.

The day before our departure, after a good English breakfast, we walked for a few kilometres until we stopped for lunch at a place with a great view of the river below us. We could appreciate the palms that fringed the Milgis margins and we could also see a few animals in the distance, particularly giraffes and greater kudu.

The final camp was a more permanent affair composed of simple reed huts fitted with mosquito nets where all our bedding was already prepared for us. I decided to go for a shower but before starting, I spotted that the two people usually in charge of the showers, were seated together looking at something and brandishing a Samburu “seme” [4].

Curious, I approached them and although we had communications difficulties they showed me laughing that they were trying to repair something that on more close inspection happened to be a wristwatch! Quite sure about the outcome of the operation I left them to it and went on to enjoy my shower.

Wrist watch fixing…

Eventually, after a very enjoyable four days it was time to return and we were taken to Rumuruti, our starting point, where we spent the night at the Laikipia Country Club (founded in 1926) where Gai barely slept as the hyraxes screamed on the roof of her cottage all night! We did not hear a thing and slept through.

It was a great experience not only because the walk was very enjoyable but also because we became friends with Gai, a friendship that lasts until today.

[1] Although I refer to them as “camels” in fact the animals that accompanied us were dromedaries or one humped camels (Camelus dromedarius).

[2] Nowadays called Wild Frontiers Safaris that also runs the Milgis Trust, see: https://www.milgistrust.com/

[3] The KiSwahili word “Sungura” in English means rabbit.

[4] A “seme” or “simi” is a Maasai word to describe a short sword with a leaf-shaped blade and a relatively rounded tip.